It is known that you have been painting since your childhood. Mentioning your sources of motivation which canalize you to the painting, what is the role of difficulties that you experience living Sweden as a refugee after moving there from Iraq during the war, in your artistic practice’s improvement?

When I first became a refugee in Sweden there was a clear before and after picture for me but as time passed those binaries started to fade and memories of a past life where intertwined with present and future lives. When one is uprooted because of war, memories become a sort of lifeline to reconstitute oneself. There is a rebuilding of ones biography in a way. That moment when I landed in Sweden as an illegal refugee marked a rupture in my biography and the aftermath is something I deal with everyday. I was there in this foreign land and the only way I knew how to survive was to erase my past memories and my lived experiences. It was a conscious decision to sweep my otherness under the rug in order to fit in. I underwent a process of assimilation. In any shape or form (socially, linguistically, esthetically) I made it my mission to become a Swede. I did this to the point where I lead myself to believe that I was white. I then went through a phase of rebelling against my “swedishness” and asserting that I was in fact an Iraqi, born in Iraq and from Iraq, trying to retrieve memories associated with that locality and with that nationhood. This is a rather common occurrence within Arab refugees in Europe. An example is that of Muslim teenage girls who prior to migrating to Europe didn’t wear a hijab yet choose to wear it once they arrive in their host country as a form of assertion. As I grew older I started questioning these very ideas of a nationalistic memory. Why was it so important to say that I came from that space? And as I look back at those ideas I think it was more a form of holding on to something that I had actively chosen to repress. This goes back to the idea of trauma in migrant consciousness and the problematics of belonging, forgetting and remembering. For me it’s not about asserting this nationalistic concept of the collective. Its rather about inscribing these memories and getting them out there and the best way I know how to do this is by painting.

Having a look at the war environment we are globally in, we see the same tragedy is continueing in a more violent and intense way. Beyond any doubt, the members of art scene are not deaf to the matters such as migration, rootlessness and refugee identity. What is your opinion about exhibitions/art works mentioning these and refugee artists?

I can’t speak for other artists but for me it’s a necessity, after all this pertains to my reality and my biography as an immigrant. There’s a whole list of artists who deal with matters concerning the diaspora and it’s a reflection of what’s going on today.

It can easily be said that the most suffering victims from the war are women. You specifically remark female image in your practice. Can we associate this with the general existing struggle on the social platform independent from the era and current scene?

I’m not sure how to answer this question. I don’t necessarily assign my figures a certain scene or time. I see them more as non specific and what I mean by that is, that they pertain to a larger collective and not only a certain group.

There are several entryways into my work although the most poignant one for me is via the corporeal. The female bodies in the paintings are repositories of various reenactments of ideas some concretely and thoroughly researched while others consist of fleeting memories particularly connected to migrant lives. An important aspect in the work is that these bodies are modeled after my personal body in terms of their chorography on the substrate. My body, my narrative and memories and encounters are a voice set within a cultural context and most importantly I feel can pertain to a larger collective.

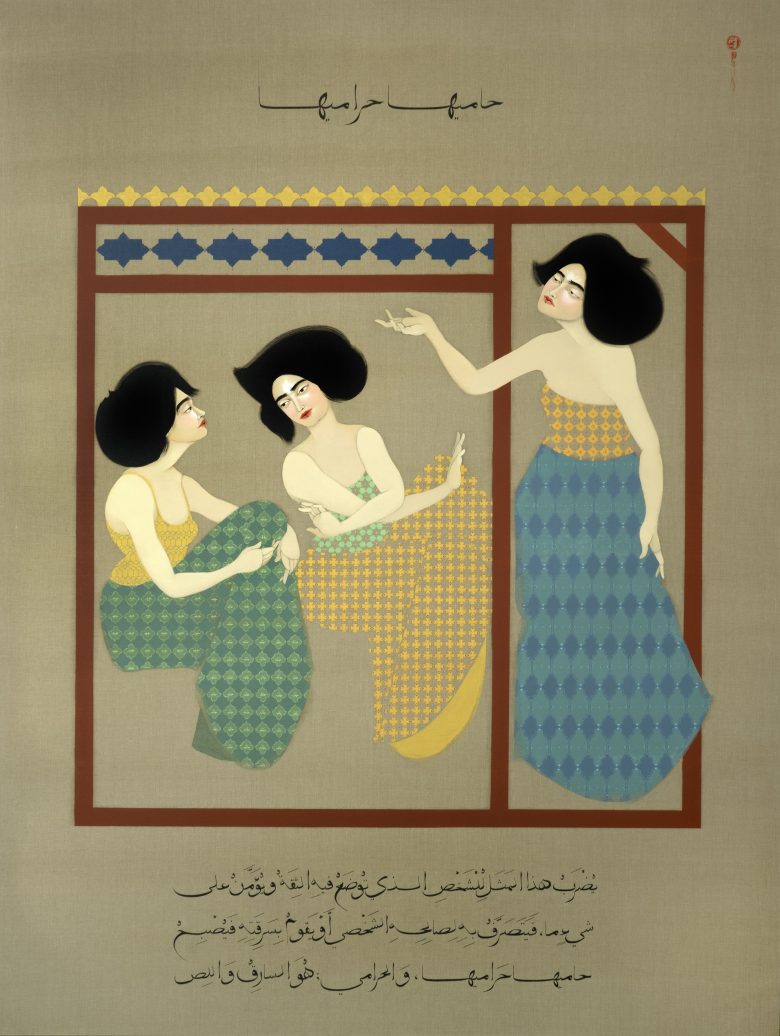

Your works have references from the wealthy cultural heritage such as Persian miniature, Greek iconography, Japan calligraphy. On which thematic backgrounds do you build these formal inspirations?

The formal elements in my work interjected in multiple ways. The figure for example is modeled after the esthetics of the renaissance. I spent 4 years in Italy where I idealized the esthetics of that era. I visited all the museums and studied the old master paintings; the technique of the sfumato, contro posto, chairo scuro etc. and these are all elements that I employ in the work. This is where “She” was born. As She started evolving I started reading texts that relate to postcoliniality and decoloniality and then something illuminating happened. I started realizing that She is a projection of a colonized body. An assimilated body, someone who was taught to think and believe that white European art history was the ultimate ideal. Her roots are that of a Eurocentric perspective that overrides anything pertaining to an other. And now as I paint her white diaphanous flesh and as she performs these various acts on the surface her body becomes a vehicle to question and to research. The miniature paintings and the geometric patterns for me are a way to establish an affinity to my culture. This is where I draw inspiration to color schemes in my work. The Japanese woodprints stand out to me because of the composition of the figure being engulfed in abstract polyhedrons of pattern. It reminds me of the Islamic tessellations I grew up with yet here there was a figure that was submerged in pattern.

It is conspicuous that you use different techniques and materials in your art works. What is the base forming your selection about technique or materials? Is there any conceptual subtext related?

I entered the “art world” by accident. My work, stripped from all research, is a raw reflection of my life as a war refugee, as a female, as a mother. It all started because I needed an outlet for survival and resistance, a surface to work against erasures that I constantly encounter. Paper was an easy material to get those concept inscribed on in the beginning. And the work at that point was overtly violent in the sense that you’d actually see a woman being hung whilst the work that followed had a more tame or rather covert brutality. The transition from paper to linen was natural after all I was using the esthetics of the Renaissance as decoys into the work and linen as a painting surface originated in Venezia. So it became a material to decolonize. I like to mimic linen with the English language, as I’m now using the colonizers language to speak about the other. Then I started introducing wood and perhaps this was an effort to get closer to the esthetics of the Middle East. It was also interesting as a campitura because it provided a grain so I needed to think about the synthesis of that with the figures. This is where the bodies started to assume a translucency as the background merged with their skins.

You had participated in the exhibition “Neighbours” at Istanbul Modern Museum a few years ago and this year Istanbul Biennale have announced the subject neighbourhood. How do you interpret the effect of geography and tradition on contemporary visual culture in point of an artist’s production? Are the matters of localness and globosity determinative criterions on contemporary art?

With the influx of refugees and the concept of the world getting smaller and smaller, I feel it’s more important than ever to think about our lives not in terms of static territoriality but in terms of movement. We all have our mnemonic itineraries and for me that appears in my paintings where the figures assume a translucency eluding to the idea of movement, of being and existing in between places.

As an artist living and working in USA, how do you evaluate the art market in Turkey? Can we say that Middle East is a fertile source in terms of both artistic production and art consumption? What is the position of Turkey for an external point of view?

The art market doesn’t necessarily reflect the artistic production and I’m not sure I’m the right person to answer that question. I can speak of my experiences relating to the art world in Turkey, which have only been positive and engaging in a very forward thinking way. I see that context as full of potential. People are taking action to resist hegemonic control via the arts. Of course there’s a push and pull and a lot of contradiction but at least there is action and that’s the driving force for change.